LEARN

Article Resources

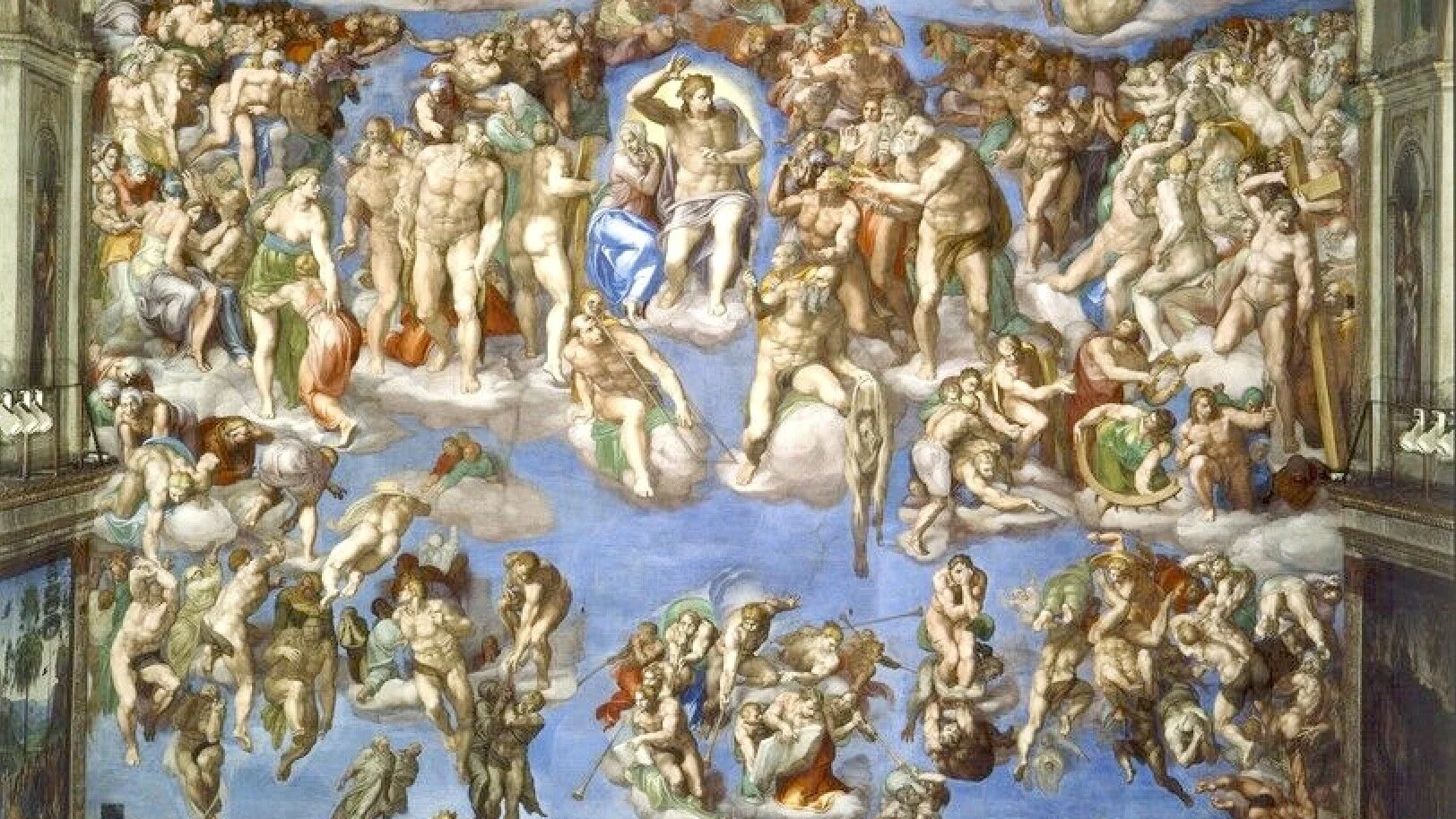

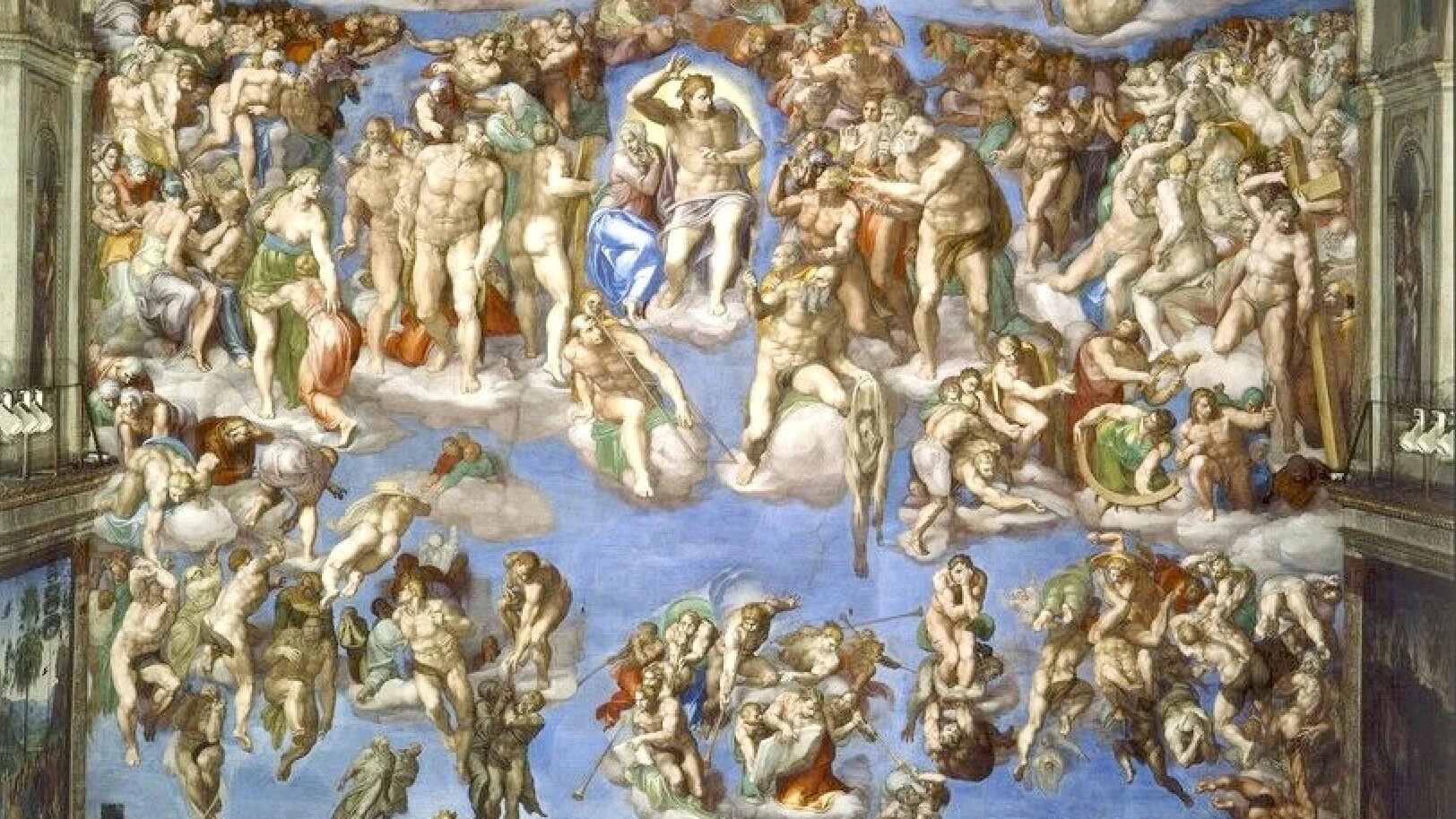

The Resurrection of the Dead and the Life in the World to Come

The Nicene Creed ends with the statement, “We look forward to the resurrection of the dead, and the life in the world to come.” The pleasures we look forward to experiencing in this life can easily crowd out the far superior pleasures we should be looking forward to in the life to come.

Nicene Creed ends with the statement, “We look forward to the resurrection of the dead, and the life in the world to come.” The pleasures we look forward to experiencing in this life can easily crowd out the far superior pleasures we should be looking forward to in the life to come.

In 1 Corinthians 15, Paul’s primary concern for his readers is not for them to believe in Jesus’ resurrection. They already believed that Jesus was raised from the dead. Paul’s concern is that they were not looking forward to their coming resurrection from the dead and their life in the world to come.

The pleasures we look forward to experiencing in this life can easily crowd out the far superior pleasures we should be looking forward to in the life to come.

Some of Paul’s readers denied their future resurrection from the dead or minimized its significance. Instead, they looked forward to being released at death from their corrupt bodies and this corrupt world so they could live forever in heaven with Jesus as disembodied spirits free from everything physical and material.

Most religious beliefs and philosophies embrace the survival of the human soul after death, and affirm that death does not end all – that there is some kind of future life after death. Among pagan religions and philosophies the teaching on the afterlife ranges from a dreaded state to be feared to a happy state to be longed for.

Greek philosophers made use of a metaphysical argument to prove the indestructibility of the soul by teaching that the soul is immortal in the sense of having no beginning and no end. Pagan views of the “immortality of the soul” usually present the spiritual part of humans as not affected by death because it is indestructible and imperishable.[1]

Most pagan views of immortality affirm the continued existence of an immaterial soul, but not the immortality of the material, physical body. At death, the immaterial soul is suddenly no longer with the material body and assumed to be in another disembodied, immaterial state. But the body remains behind and physically disintegrates.

In contrast, the Scriptures teach the value of the material world God created by affirming that immortality is not merely the survival of the soul after death in heaven with God, but the redemption and restoration of the whole person, soul and body together, at the resurrection of the dead – along with God’s final restoration of the entire physical universe in the age to come.

The Apostles’ Creed strongly affirms the centrality of the physical world in the Triune God’s person and work by its description of God the Father Almighty as creator of heaven and earth, and in its declaration of God the Son’s incarnation by being born of the virgin Mary and his resurrection as the one who rose again from the dead, to the creed’s final statement on God the Spirit’s work in the resurrection of the body and the life in the world to come.

For believers to experience immortality, their souls must be miraculously resurrected from spiritual death at their new birth, and then their bodies must be miraculously resurrected from physical death at their resurrection from the dead. The Bible teaches that when Jesus returns, all the glorified souls of believers in heaven will be reunited with their glorified bodies on earth, so they will flourish in both their bodies and souls on a glorified earth in the new “world to come.”

[1] This is not a biblical doctrine. The Scriptures teach that the human soul is created by God at conception.

[2] The early church father Augustine (354-430 AD) describes the essence of God’s salvation in Christ by using a series of Latin couplets that describe God as “Former and Re-Former,” “Creator and Re-Creator,” and “Maker and Re-Maker.”