Introduction to Paul’s Letter to the Romans Part 3: The Context of Paul’s Letter to the Romans

Steven L. Childers

A. The State of Paul’s Ministry

Toward the end of Paul’s third missionary Journey, he is in Corinth where he writes his letter to the Romans. In the final part of his letter he makes an astonishing statement – that all the work of the gospel that God called him to do in the entire eastern Mediterranean world was now complete.

He describes the vast regions where his work is fulfilled saying, “from Jerusalem and all the way around to Illyricum I have fulfilled the ministry of the gospel of Christ” (Rom. 15:19).[1] In Rom. 15:23 he writes, “I no longer have any room for work in these regions.” As a result of Paul’s first three missionary journeys, consisting of almost twenty-five years, he helped plant churches in:

Southern and Western Asia Minor (Tarsus, Pisidian Antioch, Lystra, Iconium, Derbe, and Ephesus), and

Eastern Europe: Macedonia (Philippi and Thessalonica), and Greece (Corinth).

However, Paul did not believe that all the work of the gospel was fulfilled in the entire Mediterranean world – just his work as a pioneer church planter. He knew that the churches he planted could take responsibility for their own evangelism, discipleship, mercy, and church planting ministries to continue their obedience to Jesus by “making disciples of all nations” in and through their own regions.

Therefore, Paul is at an important transition point in his life and ministry. As he looks ahead, he tells us in Rom. 15:22-29 that there are three strategic locations he sees in his next season of gospel ministry: Jerusalem, Rome, and Spain.

1. Jerusalem

During Paul’s third missionary journey he collected financial offerings from the new churches (mostly Gentiles) so he could give this collection of money to the Jerusalem churches who were suffering from severe famine. Paul frequently refers to the importance of this offering. (1 Cor. 16:1-4, 2 Cor. 8-9)

Paul saw this collection for the Judean churches as not only a way to provide famine relief, but also to help strengthen the spiritual bond between the Jewish churches in Judea and the mostly Gentile churches Paul planted. He writes:

At present, however, I am going to Jerusalem bringing aid to the saints. For Macedonia and Achaia have been pleased to make some contribution for the poor among the saints at Jerusalem. For they were pleased to do it, and indeed they owe it to them. For if the Gentiles have come to share in their spiritual blessings, they ought also to be of service to them in material blessings. (Rom. 15:25-27)

2. Rome

Paul did not plant the church in Rome. Although there has been much speculation regarding who planted it, including the Apostle Peter, the Bible does not tell us who planted the church or how it was planted. But while on his missionary journeys Paul kept hearing good reports about the Roman church, so he regularly prayed for them and longed to visit them.[2] He writes:

First, I thank my God through Jesus Christ for all of you, because your faith is proclaimed in all the world. For God is my witness, whom I serve with my spirit in the gospel of his Son, that without ceasing I mention you always in my prayers, asking that somehow by God's will I may now at last succeed in coming to you. For I long to see you … I do not want you to be unaware, brothers, that I have often intended to come to you (but thus far have been prevented) (Rom. 1:8-13).

3. Spain

However, Paul’s ultimate destination after he completes his mission in Jerusalem is not Rome but Spain. In Rom. 15:28 he tells the Roman church that on his way to Spain he wants to be with them in passing. “When therefore I have completed this and have delivered to them what has been collected, I will leave for Spain by way of you.” In Rom. 15:24 he writes, “I hope to see you in passing as I go to Spain … once I have enjoyed your company for a while.”[3]

Why was Paul’s ultimate destination Spain? It was because the people in Spain, unlike the eastern Mediterranean world and the regions around Rome, had never heard the preaching of the gospel. So Paul writes, “I make it my ambition to preach the gospel, not where Christ has already been named, lest I build on someone else's foundation” (Rom. 15:20).

B. The Purpose of Paul’s Letter to the Romans

1. Raise support for his mission to Spain

Paul needed a new “sending church”. For all of Paul’s previous missionary journeys he relied on the prayers and financial support of the Antioch church as his sending church. But now that his mission to the eastern Mediterranean world was finished, he needed a new home “sending church” for prayer and financial support as his mission shifts to the unreached people in Spain. Paul writes, “I hope to see you in passing as I go to Spain, and to be helped on my journey there by you, once I have enjoyed your company for a while” (Rom. 15:24).

2. Heal divisions between Jewish and Gentile Christians

One of the most likely origins of the church at Rome is that the Roman Jews, who were converted at Pentecost in Jerusalem (Acts 2:10), returned to Rome as Jewish Christians and began incorporating their new faith in Jesus as Messiah into their synagogue worship. Therefore, Christianity in Rome was probably birthed in Jewish synagogues, as it was in much of the eastern Mediterranean world. By the end of the first century Jewish immigrants made up a significant part of the population in Rome.

By A.D. 49, the Roman emperor Claudius expelled the Jews from Rome. In Acts 18:2 Luke tells us “Claudius had commanded all the Jews to leave Rome.” Douglas Moo writes, “The significance of this scenario for Romans is clear. Gentile Christians, undoubtedly part of the community before the expulsion, would have come into greater prominence as a result of the absence of all, or most, of the Jewish Christians. Theologically this would also have meant an acceleration in the movement of the Christian community away from its Jewish origins.[4]

By the time Paul writes to the Romans (late A.D. 50’s), the Jews returned to Rome and were a significant part of the population. Many differences arose between the Jewish and Gentile Christians – ethnically, socially, and theologically. As the church started becoming predominately Gentile, the more divisive issues included the role of the Jewish Mosaic Law (Torah)[5] in the life of the Gentile believer and the place of Israel in God’s plan for the world. Since the Roman church consisted of several decentralized “house churches,”[6] it’s likely that some house churches were predominately Jewish Christian while others were Gentile Christian.

3. Preach the Gospel to the Christians at Rome

When Paul was in Corinth, where he wrote his letter to the Romans at the end of his third missionary journey, he had just ended several intense battles for the gospel against Judaizers in Galatia and Corinth. Paul’s insights into the gospel, and how to preach and teach it effectively, were clearer to him than ever before. In light of these deeper insights and his awareness of the divisions between Jewish and Gentile Christians, Paul determined to write his letter to address both groups in Rome.

C. The Themes of Paul’s Letter to the Romans

Paul’s primary theme in Romans is the gospel of Jesus Christ. In the letter’s introduction he refers to the gospel four times

He begins in Rom. 1:1 identifying himself as “Paul, a servant of Christ Jesus, called to be an apostle, set apart for the gospel of God.”

In verse 9 he writes, For God is my witness, whom I serve with my spirit in the gospel of his Son.

In verses 15-16 he writes, “So I am eager to preach the gospel to you also who are in Rome. For I am not ashamed of the gospel, for it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes, to the Jew first and also to the Greek.”

In the letter’s conclusion, he also refers to the gospel four times.

In Rom. 15:16, he refers to himself as “a minister of Christ Jesus to the Gentiles in the priestly service of the gospel of God.”

In verses 19 he writes, “I have fulfilled the ministry of the gospel of Christ”

In verse 20 he writes, “I make it my ambition to preach the gospel.”

In Rom. 16:25 he begins his final doxology in the letter, “Now to him who is able to strengthen you according to my gospel.

In Rom. 1:17 Paul quotes the Old Testament prophet Habakkuk (2:4) describing the core foundational nature of the gospel on which he starts and builds his entire letter, writing, “For in it the righteousness of God is revealed from faith for faith, as it is written, ‘The righteous shall live by faith.’”[7]

When Paul describes the gospel as “the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes, to the Jew first and also to the Greek” (Rom. 1:16), we see his two major themes in the gospel and in Romans. The first theme is primary and vertical. The second theme is secondary and horizontal.

Primary and Vertical Theme: Personal Salvation

Paul’s first and primary theme in Romans is the good news of the universality of God’s gift of righteousness “to all who believe.” This gift is “apart from the law” (3:21) and it provides for the true fulfillment of the law (3:31; 8:4). This is the “vertical” good news of “justification by faith” Paul expounds in Romans 1-4 regarding how sinful humans can experience the power of God’s personal salvation and be declared right before a holy God through believing in Jesus Christ.

Secondary and Horizontal Theme: People of God

Paul’s secondary and horizontal theme in Romans is the good news that God’s salvation is “to the Jew first and also to the Greek.” The good news that God reconciles “all who believe” to himself without disenfranchising the people of Israel. Paul expounds the good news of this relationship of Jews and Gentiles within the New Covenant people of God in Romans 9-11.

It’s critically important to affirm the primacy and centrality of the gospel as good news of personal salvation.[8] Moo writes, “But that gospel itself, the theme of Romans, is fundamentally not about bringing Gentiles and Jews together but about bringing sinful humans and a just and holy God together … While, therefore, the focus on Gentile inclusion is a welcome correction to a tendency in some forms of the Reformation tradition to submerge it too deeply below Paul’s concern with individual salvation, we think the tendency in much recent scholarship to elevate it to the level of the central theme of Romans is an overcorrection.” [9]

Paul’s Multifaceted Gospel

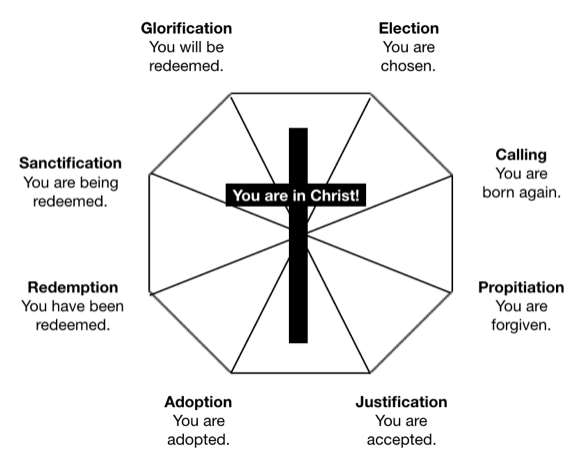

The gospel is the broad concept that comes closest to describing the core of Paul’s beliefs and theology in Romans and all his New Testament letters. Paul’s gospel is multifaceted including not only the good news of justification through Jesus’ righteousness but also propitiation (forgiveness) through Jesus’ blood.

Paul’s gospel also includes the good news of election, adoption, regeneration, redemption, sanctification, and glorification. It’s good news of not only a new standing before God, but also a new heart (nature) from God by his Holy Spirit, and a new body and world from God when Jesus returns to make us and all things new.

The various biblical terms and resultant images describing salvation display different facets of the gospel – reflecting the multi-faceted spiritual blessings God promises to everyone in union with Christ – that is the highest blessing of the gospel from which all the other gospel blessings flow.

The many facets of the gospel should not be seen as separable, but as unique dimensions of salvation as a whole, as various facets of a multi-faceted jewel. A full understanding of any particular facet of the gospel jewel comes only by seeing that unique part of the good news in light of the whole.

The Apostle Paul did not preach all the gospel blessings every time he proclaimed the good news of salvation in Christ. Instead, he seems to have selected specific aspects of the gospel he believed would be applicable to his audience’s specific needs and problems. The English Puritans also seemed to follow this approach when preaching and teaching the gospel. Commenting on Puritan Richard Sibbes’ gospel preaching in his classic work, The Bruised Reed, William Black writes,

Only when the disease is properly diagnosed can the right cure be applied. And having thus expounded man’s desperate state and need before God, Sibbes proceeds to describe and apply God’s cure. To this end, Sibbes focuses our attention on Jesus. And as a jeweller examines his diamond facet by facet, in a light which makes his stone dazzle, so Sibbes bids us look on Christ in the light of God’s word, where we see refracted through the facets of his character and offices a rainbow of comfort and hope and mercy (emphasis mine) (1988:49).

[1] Illyricum includes today’s Albania, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Croatia.

[2] Aquila and Priscilla were in the Roman church and came to Corinth when Paul was there – probably because of the persecution of the Jews in Rome under Claudius. Therefore, many of the firsthand reports about the Roman church to Paul were probably from them.

[3] We do not know whether Paul fulfilled his intention to visit Spain. The early church leader Eusebius believed that Paul’s appeal to Caesar was successful – allowing him to spend some years in Spain before he was again imprisoned and sentenced to death. Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 2:22 There are several official and popular traditions of Paul’s missionary journeys to Spain held by the church in Spain.

[4] Moo, Douglas J. A Theology of Paul and His Letters: The Gift of the New Realm in Christ. Edited by Andreas J. Kostenberger, Zondervan Academic, 2021. 21

[5] The New Testament as we know it did not yet exist, so their Scriptures were only the Jewish Old Testament, often in Greek (Septuagint).

[6] Paul writes to Priscilla and Aquila, “Greet also the church in their house” (Rom. 16:5).

[7] New Testament scholar F. F. Bruce translates this, “It is the one who is righteous through faith that will live.”

[8] What is often called the New Perspective on Paul (James Dunn, N. T. Wright) wrongly pits the secondary, horizontal/corporate nature of salvation and justification against the primary, vertical/personal nature of salvation and justification, calling into question the biblical necessity of personal faith in Christ for the salvation of individuals. The problem with New Perspectives teaching on justification is not what it affirms, but what it denies. New Perspectives proponents like N. T. Wright believe and teach that the doctrine of personal justification by faith, promoted by the Reformers like Luther and Calvin, is not biblical, but a reflection of Medieval thought categories.

[9] “Moo, Douglas, J. The Letter to the Romans. Second Edition, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2018. 26-27